Reminder: these are show notes that should be read in conjunction with the podcast. Do not expect these notes to be a polished research report. Enjoy the episode and listen wherever you get your podcasts!

YouTube

Spotify

Apple

Chit Chat Money is presented by:

Public.com!

Public.com has just launched its new high-yield cash account, offering an industry-leading 5.1% APY*. No fees, no subscription, and no minimums or maximums–just 5.1% interest on your cash. Sign up today at https://public.com/chitchatmoney

*As of 12/14/2023, annual Percentage Yield (APY) is variable and may change without notice. A High-Yield Cash Account is a secondary brokerage account with Public Investing, member FINRA and SIPC. Funds from this account are automatically deposited into partner banks where they earn a variable interest and are eligible for FDIC insurance. Neither Public Investing nor any of its affiliates is a bank. US only. Learn more.

Show Notes

“Two people inside Bridgewater – one in investment research, the other a lowly information technology grunt – had higher believability scores than Dalio himself. People were beginning to whisper about it.

McDowell explained to Dalio that this was a sign the system was working, that Bridgewater was fishing out the pockets of talents in its ranks – exactly as Dalio had asked him to do.

Dalio’s voice made no secret of his irritation. Why doesn’t believability cascade from me?

McDowell thought back to Dalio’s index card drawing. He realized that Dalio hadn’t been sketching out the mere concept of believability on top. He had drawn himself quite literally at the head, bestowing believability to all beneath him.

The fix was obvious. McDowell assigned an underling to go into the software and program a new rule. Dalio himself would be the new baseline for believability in virtually all important categories. As the original top-most believable person at Bridgewater, Dalio’s rating was now numerically bulletproof to negative feedback. Regardless of how everyone else at the firm rated him, the system would work to keep him on top.”

That is an excerpt from The Fund: Ray Dalio, Bridgewater Associates, and the Unraveling of a Wall Street Legend by Rob Copeland.

We read the book over the holidays, thought it was fantastic, and wanted our listeners to learn more. So, we recorded an hour-long podcast covering the secretive hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, its eccentric founder Ray Dalio, and all the wackiness uncovered in the book.

We hope you enjoy it. Here are some of our notes from today’s episode. Listen to the full podcast to get every insight.

Part 1: What is Bridgewater Associates? Who is Ray Dalio? What story does he tell the world about the company?

(Brett) Bridgewater Associates is currently estimated to be on of the largest hedge funds in the world, with close to $100 billion in assets under management (AUM). It is one of the most powerful financial institutions in the world and has been for decades. It has relationships with some of the most powerful business, economic, and government actors in the world. And yet, how it actually works has been a mystery for years.

Until now, with the release of the new book The Fund which chronicles what actually goes on at this mysterious hedge fund.

But before we discuss Bridgewater at length, we need to talk about Ray Dalio, its founder and eccentric leader. As you will see after listening to this episode, Bridgewater is Dalio and Dalio is Bridgewater. And yes, we are going to be discussing The Principles, the fulcrum of this entire operation. Or, maybe, how it is unraveling.

Dalio was born just after the end of WWII in Queens, New York. He was an only child and grew up in Manhasset on Long Island. As a child, he became a caddy at the Links Golf Club, where he started working for the financial elite of the time (assuming the 1960s or so). Most of the sourcing here is from the book.

As a caddy, he met a rich couple from the finance world. He became very friendly with them and they asked him to help spend time with their son.

“He understood what relationships were about way before anyone else did, and he used it to his advantage” - Caddy sourced for the book

His mom died when he was 19 from a heart attack. He was a bad student who ditched school to surf. He went to a small, easy to get into school called C.W. Post. There, he started getting straight As and ended up working in New York on the stock exchange for a summer. This and his relationships formed as a caddy helped him get into Harvard Business School.

Building Bridgewater

After HBS, Dalio started up Bridgewater Associates. Due to his connections with wealthy families in New York, they originally had a strategy of “wealth preservation” and “not losing money” in the late 1970s and into the 1980s.

Famously, Dalio implemented a soybean/corn futures contract with McDonald’s to help stabilize their chicken costs (soybean/corn are the feed that chickens eat that gets turned into McNuggets).

Hot take: Is this really that novel of an idea? It is part of the Dalio “lore” that I’ve seen used again and again to tout that he is a genius. I fell for it early in my career listening to podcasts either discussing him or with him as a guest.

This, along with various media appearances and his beginning of a markets commentary newsletter (sent by fax before email was invented/popularized). He built up a great reputation and started charging upwards of $3,000 per month for his “research package” or close to $10,000 a month today.

And a tale as old as time, Dalio was consistently bearish. Very bearish. In 1982 this is what he said (quote from the Fund):

“Since 1800, Dalio said, the United States had experienced fourteen major depressions, all following the same historical patterns. The fifteenth was plainly imminent.” - 1982

Even though the 80s were a big bull market, this consistent doom and gloom from Dalio was helpful when the Black Monday crash of 1987 occurred. He hired a marketer as one of his first-time employees and in the announcement said that the firm had $700 million in AUM. But apparently, this was greatly exaggerated:

“Streit [the marketer] knew that eye-popping sum wasn’t even close to correct. He assumed that Dalio had counted the assets of everyone who received a copy of Bridgewater’s newsletter – even though most had no money with the firm…Streit learned quickly that to his new boss, appearances matter.”

But the reputation really started improving in the 1990s, which you might call one of the two Bridgwater heydays (the other during and immediately after the GFC). In 1991, Bridgwater launched its “Pure Alpha” fund (great name) which was supposed to generate strong absolute returns year after year. In its first few years, it crushed the market and never had a down year.

By 1999, it had $3 billion in AUM by itself and had doubled its AUM every year since its inception. It didn’t beat the market every year, but it was extremely consistent

So what was so special about Pure Alpha and what Bridgwater was implementing/pitching to clients? It was a rules-based, systematic approach to money management with major diversification across what they pitched as “uncorrelated” assets. This meant using market history and quantitative measures as a guide.

Funny enough, the fund would do quite well during one of the major U.S. bull markets even though virtually every year Dalio would call for an upcoming economic collapse. One of his colleagues even introduced him in a meeting once as “someone who has called 15 out of the last 0 depressions” but Dalio apparently wasn’t amused.

So, credit to them. They built a solid product in the 1990s around the Pure Alpha strategy, had great marketing, and harnessed Dalio’s relationships with virtually every sovereign wealth fund in the world (yes, even in the Middle East, Russia, and China). Life was good and the fees started to roll in.

And then we move into the 2000’s. In the dot-com bubble bust, Pure Alpha lost just 1% in 2000 and then gained 9% in 2001. AUM just went into overdrive:

“The firm grew from $33 billion in AUM in 2001 to $167 billion in 2005”

However, like always, Dalio was getting bearish in 2005. He was right for the right reasons this time, foreseeing the great financial crisis and a commodity price boom. It took a few years, but he was right and “rang the bell” on the mortgage loan troubles. However, he was very inconsistent in what he said the impact would be when talking in the media. In 2008, the fund was up 9% while the average hedge fund lost 18%.

Discussion question: Thoughts on the early-to-middle days of Bridgewater? What surprised you? Did they just get lucky?

But then…things started to stagnate

Part 2: What is truly going on at Bridgewater? According to the book. Is it a fraud?

Not a whole lot of investing. Out of the roughly 2k employees at Bridgewater at its peak, only 20% were involved in the investing side of things. The rest was a business about building basically the perfect business.

In fact, it’s a common trend throughout the book. People would apply and get the job at Bridgewater, then realize they had no idea what was going on with the investment portfolio. For the vast majority, they had no involvement with investments whatsoever. Instead, it was building the “great investing machine” of Bridgewater.

Every “analyst” would go through Principles Training. This was what most of the book was really about. Dalio had created a list of what he called “Principles”. And he wanted this to basically be Bridgewater’s version of the bible. If anything went wrong, if there was ever any dispute, they would look to the Principles to see how to deal with it. He had every employee equipped with an iPad that had a digital version of the book. Analysts took exams on the Principles. It was meant to be sort of this governing document for everyone at Bridgewater to live by. Instead, what it really did, was foster a culture of back-stabbing and confirmation bias for those at the top.

Before we dig any further into the culture, I want to get this right out of the way. Bridgewater was not a fraud. It’s weird as hell, it’s a cult, maybe even a religion, but it wasn’t a fraud. In fact, many people tried to investigate it. Bill Ackman questioned it, Jim Grant went on record saying “We will go out on a limb, Bridgewater is not for the ages”, and even Harry Markopolos who uncovered the Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme tried to investigate it. The SEC investigated them. And here’s what they found: “The world’s biggest hedge fund used a complicated sequence of financial machinations – including stock options and other relatively hard-to-track trading instruments — to make otherwise straightforward seeming investments.”

In truth, it was not an investment machine. Greg Jensen (pretty much the 2nd most important person at the company) at one point said “I could run this firm on a single spreadsheet”. On page 240, the book describes it as this “There was essentially no grand system, no artificial intelligence of any substance, no Holy Grail. There was just Dalio, in person, over the phone, from his yacht, or for a few weeks many summers from his villa in Spain, calling the shots.”

He would get important information from world leaders and trade on it. He’d buy their currency, short it, buy oil, short it. Whatever it was. He had good information, oftentimes from world leaders. That’s what Bridgewater truly was doing.

Then there was what Ray Dalio wanted people to think Bridgewater was doing. He wanted people to believe Bridgewater was this highly automated idea meritocracy that produced wonderful investing results. To do this, he built internal systems that employees lived by. The most important was the dotting system. Everyone had a believability score that was determined by their colleagues’ opinions of them. That means if you don’t like someone, you can down-dot them. Or publicly complain in the “issue log”.

Dalio was also maniacally focused on “radical transparency” so in order to do this, Dalio had video and audio recording tools everywhere. If you were at Bridgewater, you were being recorded. And it was also publicly accessible via the “Transparency Library”.

Basically, a common sequence of events happens throughout the book over and over. Someone does something wrong, doesn’t get a task done in time, talks bad about a colleague, talks back to Ray, questions the Principles, you name it. Once Dalio was aware of this (and he had teams of people just designated with finding bad actors), he would have a “trial”.

In the trial, which was always recorded, he would play the tape, attack the person verbally til they cried, then attack them for having an emotional reaction, and then typically fire them. If you think it’s weird to have the questioner be the executioner, you’re right, it’s really weird. Here’s one example of this that actually didn’t end so well for Bridgewater.

Greg Jensen was spending alone time and getting into a physical relationship with another lower employee named Samantha Holland. Apparently, after going out to drinks after work, colleagues saw them go home together, so they reported them. Jensen said they hadn’t gotten physical, Holland said they kind of had. So, Dalio had the ethics committee (which is just a team of 3 men) hold a “Trial”.

Basically, they disagreed on their versions of events, even though Holland had hotel receipts and people had all said they were being affectionate. But Dalio couldn’t say whether she was lying or not because Jensen had such a high believability score. Dalio declared it a mistrial and then asked Holland to voluntarily leave and accept several months of severance. Holland got a lawyer. Holland’s lawyer spoke to Dalio on the phone and here’s what the book says: “Not only had Dalio ignored all standards of procedure for investigating such workplace conduct by investigating it himself, outside of HR, he was told but he’d potentially impugned Holland’s reputation. The ethics committee might have a catchy name, but it was a legal nightmare. In no universe, Holland’s attorney said, was it appropriate for three older men untrained in such matters to question a woman about her relationship with the CEO.”

Bridgewater settled and gave her 3 years of her salary to leave.

The Dotting System:

It’s honestly a little difficult to do justice to just how stupid the dotting/rating system was. There are countless examples of how this creates just the absolute worst incentives. But I want to read this email from someone at the company. His name was Kent Kuran. He was a junior analyst who had been there for 19 months and was getting sick of the culture.

Here’s how his email reads:

Subject: Exit Interview: Kent Kuran

Reason for Leaving: Career Change/Performance

Comments:

The immediate reason for leaving is losing my MA box due to Ray and David’s data points on me…

Somewhere between watching the 4th and 5th manager in my neighborhood be deemed inadequately conceptual, unable to synthesize, etc., while performing what would be considered modest responsibilities at another firm, the principles lost some of their magic for me…

Knowing that any hour of the day Ray might respond unpredictably to a daily update or that any casual comment in a meeting might lead to a seminar about how one’s “thinking is poor” generates tension and fear. It probably doesn’t help that 50+ percent of “management training” consists of watching the “sorting” (could you find a more Orwellian word?) of one once respected colleague or another…

There’s an unhealthy drive to the negative that’s often debilitating. Just a few weeks ago I literally couldn’t think of any significant strength other than the charitable “hardworking”. People seemed to be on the prowl to discover my weaknesses but strengths were underappreciated.

Bridgewater was sold to me as an empowering place, where relatively young people can challenge the status quo and make a big impact. Fast-forward and it was drilled into me that it’s bad to have opinions to the point that I felt like a catholic schoolboy looking at porn whenever a nonconventional thought came into my head…

On the perks and social end, the place beat expectations.

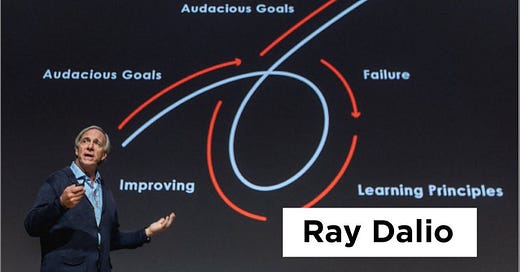

Early on in the book, they describe how the ratings system was getting setup and it was perhaps the moment where you got a sense of who Dalio really was. Dalio asked McDowell to build this ratings system for everyone in the firm. Where based on a number of factors, everyone would get a 1-10 scoring on believability. He was obsessed with it. He wanted it to show how much of a meritocracy the company was.

But when someone scored higher than him. He told McDowell the system didn’t work. McDowell had to go in and hard-code Dalio’s believability score to be the highest.

Discussion question: What did you think about the dotting system?

(Brett) Fund returns since 2011 have been terrible. AUM is significantly down from its peak, although the fees have been nice and fat. Run what 2 and 20 earn you on a $100 billion AUM fund that has a 10% up year (or even just flat). You can see why Dalio is one of the wealthiest people in the world.

Discussion question: Why do we think the fund performance faltered post-GFC? Was it all on the treasury bet ending?

(Brett) It seems to me that a lot of what Bridgewater was actually doing is trying to be as “neutral” to the market as possible while also riding the three-decade bull market in U.S. treasuries. When that essentially ended in 2010 or so when ZIRP started, Bridgwater’s “edge” ended.

“Another moneymaker for Bridgwater was Bob Prince. Dalio had delegated the lion’s share of research on bonds, or fixed income, to his longtime colleague. Prince made bonds, particularly U.S. Treasuries, considered the safest of all, a mainstay of Bridgwater’s client accounts. The move proved prescient and profitable. Treasuries went on a long streak of strong performance, up double digits some years, including in 2000 when the stock market dragged badly and busted currency bets weighed on the rest of the Bridgwater portfolio”

Part 3: Our thoughts on Bridgewater, the Principles, and favorite parts of the book

(Ryan) It sounds obviously dystopian. Like you finally muster up the courage to say something in a meeting and everyone pauses looks down at their iPad and downgrades you. All of a sudden when they decide to do some company “Sorting”, you’re the first to go because you got downgraded.

Dalio strikes me as a great salesman. Maybe one of the best ever. But someone who is so full of himself and surrounded by yes men that he has no idea how wrong he is sometimes. I think the best examples of this are when Dalio gets into arguments with subordinates and then asks everyone to raise their hand if they agree with the person Dalio is arguing with. Obviously, no one is going to raise their hand. But then Dalio goes “See, no one agrees with you”.

The other thing that I keep getting hung up on is how contradictory many of the principles are. There’s no way to have 375 principles that don’t contradict each other. I’m sure you could find some principles to support any action you did.

After reading the book and reading Principles a long time ago, I came away confused about who Bridgewater’s customers are. Like it’s the clients, but they dedicate so much of their business to serving absolutely no one. Like why do all the employees need to take exams on the Principles? How does that help their clients?

I’ll use this passage from the book to reiterate that. At one point, BW brought in Jon Rubinstein to be CEO. Rubinstein had been a former executive at Apple and they actively tried to recruit him. I think he was paid something like $25 million a year or something crazy to come to Bridgewater and improve the “technology”. But no amount of expertise could solve it. The book says “At Apple, Steve Jobs had taught Rubinstein to keep a laser focus on the end customer. The North Star of the company was to create helpful products that delighted customers. To Rubinstein, Dalio seemed focused on delighting himself.”

(Brett) I think the book is great. It was a big “They are who we thought they were” moment for me. Plenty of smart people I follow in the finance world would always claim that Bridgwater was sort of a scam and pure marketing BS, but now I understand what is actually going on. The Principles are frankly incredibly stupid (sorry Dalio, you can wipe your tears with the billions in fees you’ve earned).

But Dalio is extremely smart about building his brand among people who are not curious enough to investigate (or read this book). For example, this was me five years ago or so. I watched the famous YouTube videos about the “economic machine.” At the time, I thought he was extremely smart. A hedge fund manager explaining the economy, something that was confusing to me. He was very convincing. He also has constant media appearances and the like that made me think he was one of the investing “geniuses” out there on par with Buffett.

And plenty of others have too:

My favorite parts of the book are when he tries to focus everything on building the perfect business system. It is very confusing, but shows how far the company has gone from actually making investments. It is a great lesson on how not to run a durable business.

I also liked the discussions around where Dalio gets his AUM. These are – shall we say – perhaps not the friendliest governments in the world. There is even some juicy stuff about meeting Putin. But most importantly, it talks about his long-running relationship with China. I was always surprised at how bullish Dalio was on China. He loved them in interviews even though it clearly looked like a potential debt bomb (which is turning out true, by the way). Now I see that he was just beholden to his investors.

Discussion Question: Favorite hilarious “principle”?

(Brett) Dalio’s favorite “principles” from 2023: https://x.com/RayDalio/status/1741621077842047177?s=20

(Ryan) “Sometimes you need to be able to shoot the ones you love and we need to love the ones we shoot.”