Nick Sleep: How The Secretive Investor Crushed The Market With Concentrated Compounders

20% returns for 20 years, you can learn a lot from this guy

YouTube

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Link to Nomad Letters: https://igyfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Full_Collection_Nomad_Letters_.pdf

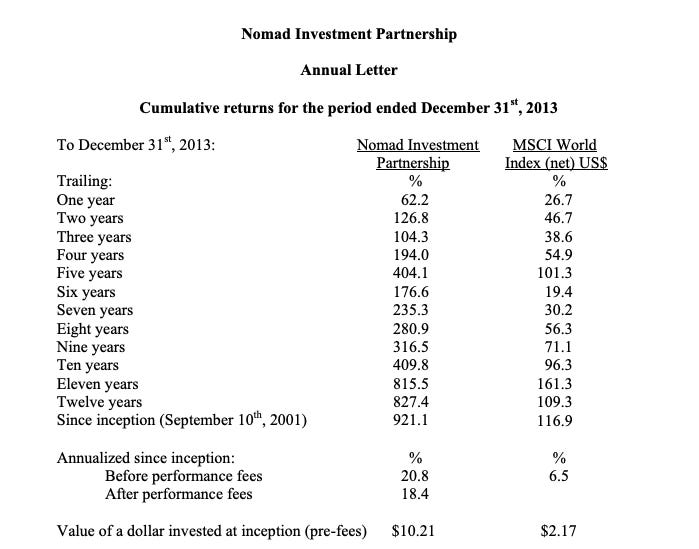

Who is Nick Sleep? Why do people study him today? What were Nomad’s Returns?

The Nomad Partnership was an investment fund started in September 2001 and wildly enough was actually started on September 10th. Yes, that is one day before 9/11. It was originally run as a subsidiary of Marathon Asset Management (where the two portfolio managers worked) but then spun out as its own fund. It closed in 2014.

The fund was run by Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria. Both were private and did not do much public communication. Most of the letters written (200 pages worth) are from Sleep, although it is not clear how much were his own ideas vs. Zakaria’s.

People began to study the partnership when bootleg files of their investing letters were uploaded online. They are well-written and indicate great performance through turbulent market periods. The fund generated around 20% returns for investors and likely would have put up 20% returns for 20 years through an update estimated back in 2021.

However, due to the outperformance of the three majority holdings at the time of the fund’s closure (Costco, Amazon, and Berkshire Hathaway), it is likely that 20% IRR has been bumped up even higher.

Either way, the fund did quite well over its 13-year run.

Investors – including ourselves – are fascinated with Nomad’s transition from cigar butt international investing (the majority of investing the first few years) to permanent, “never sell” investing (how and why they ended the fund). It also helps that they put up great returns at a decent scale.

It made around $2 billion total for its clients.

So, why do they invest the way they do? How did they beat the market over the long term?

Lets go through some of the investments that he outlined

Costco: Here’s how they summarized the power of Costco’s business model:

However, they weren’t the first ones to discover that Costco was a good business (it traded at 25x earnings when they were first buying). But they did have a unique way of rationalizing the valuation:

Sleep says “Heuristic 2: “it’s expensive at 24x earnings”. Really? Net income is a small residual, as discussed above. The firm could earn Wal-Mart margins by taking pricing up a little, in which case the firm would be on 11x earnings, but would it be a better business as a result? We think not, if it allowed the competition to catch up.”

Amazon: The Amazon investment was a lesson in replicating the “scaled economies shared” idea for Costco. Nomad saw that Amazon was trying to keep prices low and create the retail subscription flywheel for e-commerce back in 2006. It ended up being one of the largest investments in the fund that they held through the end. Sleep recommended investors keep holding this as one of the three majority holdings at the time of closure, and it ended up being a huge position in his personal account.

However, Sleep actually sold some of his Amazon back in 2021. Why? Because it was getting so large (I guess you truly don’t never sell).

Was he also worried about a change in culture at the company?

“Complexity is one of the main reasons firms fail as they try to grow” is a quote from the letters. Sleep also talks a ton about simplicity for a business being important (using Amazon back in the day as an example).

But isn’t Amazon the opposite of this today? Has Amazon strayed from the scaled economies shared?

Air Asia (mistake) Air Asia is/was a Southeast Asian budget airliner. I believe they targetted the stock because it looked similar to RyanAir and had a “scaled economies shared” strategy.

“Air Asia is Asia’s largest low-cost airline and is probably the lowest cost airline in the world. The firm has borrowed heavily from Southwest Airline’s model of operations (a point-to point network configuration, on-line ticket sales, no reserved seating, one plane type). The effect is that costs including fuel are around 3c (US) per seat per kilometer (as of December 2007). Costs are very important when the product is, more or less, an undifferentiated commodity, and 3c compares with around 4.5c at Ryanair, 5.5c at Southwest or more importantly 4.5c at rival Malaysian Airlines”

The problem is, Air Asia did not work out as an investment. I can’t figure out exactly why and the stock charts you can find are not very coherent (usually not a good thing) but it seems like a mistake they made. In the letters, they used to group in Air Asia with the other three big holdings, so it looks like they had a lot of confidence.

What lessons can we learn from this mistake in Air Asia?

Frameworks that he uses

Scale Economies Shared:

Price to Value Ratio: This one is a pretty simple concept, but it’s basically the price of securities in their fund compared to what Sleep and Zakaria thought those securities were worth. So in his first letter he states “When we evaluate potential investments, we are looking for businesses trading at around half of their real business value”, that would imply a price to value ratio of 0.5. And this was sort of their measuring stick. They compared new ideas to their price-to-value ratio. So let’s say they found a stock trading for $1 that they thought was worth $3. That would be a price-to-value ratio of 0.33x, and would be worth adding to the portfolio considering it was below the overall portfolio’s Price-to-Value ratio.

Robustness Ratio: What percentage of a firm’s excess capital is going to shareholders vs. customers vs. employees? And they would actually build a pie chart for it.

Here was Geico’s Robustness Ratio:

And here was Costco’s Robustness Ratio:

The overall idea here was that if you return your spoils back to customers, they will return it by more. It’s the business equivalent of deferred gratification. By passing up on taking that cash for themselves today, there will be significantly more to go around in the long run. In my opinion, and it might vary depending on the business model, but the best approach to allocating capital is to strike a balance between the various stakeholders and the younger you are as a company, the more you have to favor the customers.

What did he get right about running a fund?

(Ryan)

He wasn’t eager to pull in new capital. He was willing to wait until the opportunity set was ripe. Not everyone can afford this luxury, but this is one of the most difficult things about running a fund. When things are going well, that’s when the fund is the easiest to market, but that’s not when you want fresh capital.

Expectation setting. He did an awesome job of this. And he basically said all throughout his letters something along the lines of “if we can’t find opportunities, there’s a chance we shut this thing down.”

Not capitulating on price just because the opportunity set wasn’t great in equities. During their half-year letter in 2006, Sleep basically says “We aren’t taking on any new money because we can’t find anything at the moment that reduces the price-to-value ratio of the fund”.

(Brett)

I think the fee structure was smart. They had a tiny management fee to pay for overhead costs and then a performance fee for each investor once the investment hit a 6% annual hurdle based on the timing of the investment. This is similar to how the Buffett Partnership was run. Not only is it a fair way to run an investment fund, but it helps mitigate investors getting upset at a period of underperformance (no fees are paid and can actually be clawed back), which is detrimental when running a fund. You don’t want investors pulling out when the market is in shambles.

Communicating expectations for how the investors would act, telling them they are smart and therefore will not be stupid when the market is falling. While doing so, it set the table for a smooth operating period during the GFC or other periods of underperformance. Not only did investors not pull out, they actually leaned in when the fund opened up to new subscriptions. They also talked consistently about lowering fees as much as reasonable in 2005, very early on.

Repetition. When reading them all in tandem, this can get boring, but Nomad was great at repeating the tenets of their investing philosophy so people understood why they were doing what they were doing. Buffett does this as well.

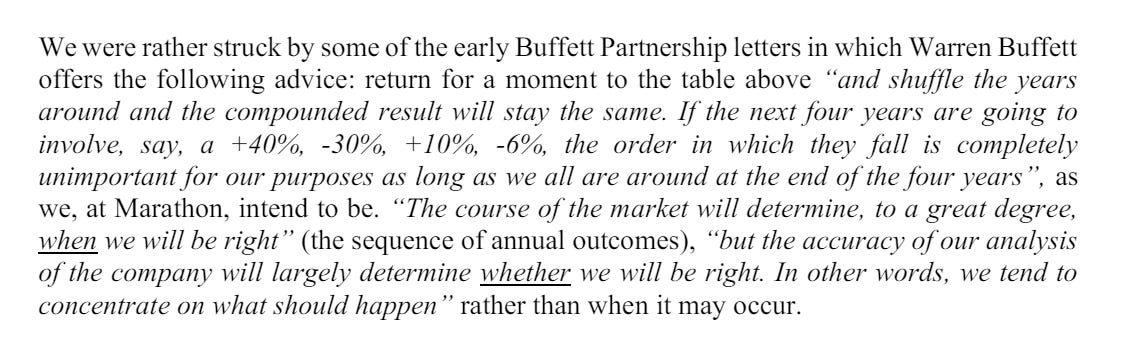

From page 22 of the letters file:

Favorite parts of his investor letters

(Ryan)

I like this approach to analyzing companies, and it’s probably something I need to do more of. Page 16: “We can, for example, buy common shares, preferred shares, debt or convertible bonds. In analyzing a company, we assess the merits of investing in all levels of the capital structure.”

Here’s what Sleep describes as the company’s most common mistake, aka empire building. Page 30:

He asks what the perfect business looks like. Here was his response (Page 52):

(Brett)

Talking about how cheap the market was in the dotcom bubble for small deep value stocks:

Page 30 “According to Empirical Research Partners, an independent research boutique in New York, in 2003 the ratio of capital spending to revenues at US companies was at its lowest level since at least 1965 and free cash flow the highest compared to market capitalisation. The predominance of free cash flow has allowed market interest rates charged to the most indebted businesses (the so-called junk bond spread), the highest for a generation between the end of 1999 and 2003, to decline to more normalised levels and it is the shares of businesses perceived to be in the worst condition that have bounced the most. Nomad has been heavily concentrated in this category.”

Was the style shift from deep value to permanent holdings simply due to the change in where the opportunities lay in those time periods?

Talking about how they do not care about the index:

Page 103 “Zak and I have witnessed many investors make terrible investment decisions from thinking via the index. The most common mistake is to view the index (indeed any index?) as a riskfree “home”. That this disposition still exists after the irrational index bubbles that preceded the Asian crisis and technology collapse may be testament to the strength of the marketing skills of the financial establishment. Once the index is seen as risk free the mistakes that follow cascade and include: requirement to have an opinion on everything inside the index regardless of one’s circle of competence, an unwillingness to invest in other better opportunities, and over diversification. These three mistakes destroy a lot of capital. We came across one country manager’s report claiming that although his country had done poorly it had proved valuable as a “portfolio diversifier” in a global fund: Many a furrowed brow these last few weeks figuring out what that means! Even so, index relative funds are the industry norm because they sell. And they sell because the client does not trust their manager with the keys to the Ferrari. It is a ghastly Faustian pact”

Reiterating the advantage of patience if you have the analysis on the business correct:

Page 104 “Good investing is a minority sport, which means that in order to earn returns better than everyone else we need to be doing things different to the crowd. And one of the things the 105 crowd is not, is patient. Readers of our letters (there must be some) may be familiar with the notion of the equity yield curve, and our thoughts were covered in an interview for the Outstanding Investor Digest (reprints available upon request, do ask Amanda) a few years ago. (In brief, the equity yield curve is a concept that argues that patience has a value, and that returns increase with time in the equity market as they do on a normal bond market yield curve). In the bond market the higher yield is there to compensate for the increase in risk that the principal will not be repaid, or that the principal may be devalued by inflation. That is not how it works in the equity market: in our opinion business outcomes can be more predictable several years out than they are in the near term. For example, we have no idea where the market will end this year but given corporate strategies, capital allocation and starting valuations, I think we have some idea of how our companies will evolve over the next few years. In other words (at this point economics students may wish to cover their ears) the return from investing in shares can be both increased and de-risked by time”

Only 5% of management teams act rationally:

Page 171 “Judging by our hit rate with companies interviewed, Zak and I would guestimate that fewer than five percent of publicly listed firms do what they think is right, rather than what they think plays well with the outside world (media, Wall Street, investors). Even so, the vast majority of Nomad’s firms do what is right long term. But I suspect we have a predilection for such people.”

What lessons can investors learn from The Nomad Investing Partnership? What lessons are we taking for our own portfolios? Closing thoughts.

(Brett)

Here is what I want to take away from the Nomad investment partnership:

To beat the average investor, you have to be different than average. If you are just piling into what is popular on Wall Street, the financial media, or actively trading it is likely you will do average (or worse).

Ignore the index completely.

Stay patient. One of the only advantages small-time investors have is patience.

When you find a great company that you understand and can buy at a reasonable price, it should take a huge overvaluation for you to sell that stock. An example of this is Sleep selling Amazon in 2021, according to the Richer, Wiser, Happier book.

(Ryan)

Well this isn’t a real novel takeaway, but hold your winners. Here’s a line from page 121 of his investor letters: “In previous Nomad letters we have argued that the biggest error an investor can make is the sale of a Wal-Mart or a Microsoft in the early stages of the company’s growth. Mathematically this error is far greater than the equivalent sum invested in a firm that goes bankrupt. The industry tends to gloss over this fact, perhaps because opportunity costs go unrecorded in performance records.”

*Side note: I think I’m going to adopt a new philosophy from studying these investors. Every stock I buy, I will at least hold for 3 years. The outcome in that timeframe is so uncertain, but by that point, I’ll have a better idea of what companies are “winners”. Not purely based on price movements but where you can see the improvement in results.*

One of the worst things an investor can have is a management team that is self-serving.

Don’t capitulate on price. Wait. Hold treasuries in the meantime if you have to.

When there is a big reinvestment runway, companies have more capacity to allocate excess capital to customers over shareholders.

Chit Chat stocks is presented by:

Public.com just launched options trading, and they’re doing something no other brokerage has done before: sharing 50% of their options revenue directly with you.

That means instead of paying to place options trades, you get something back on every single trade.

-Earn $0.18 rebate per contract traded

-No commission fees

-No per-contract fees

Options are not suitable for all investors and carry significant risk. Option investors can rapidly lose the value of their investment in a short period of time and incur permanent loss by expiration date. Certain complex options strategies carry additional risk. There are additional costs associated with option strategies that call for multiple purchases and sales of options, such as spreads, straddles, among others, as compared with a single option trade.

Prior to buying or selling an option, investors must read and understand the “Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options”, also known as the options disclosure document (ODD) which can be found at: www.theocc.com/company-information/documents-and-archives/options-disclosure-document

Supporting documentation for any claims will be furnished upon request.

If you are enrolled in our Options Order Flow Rebate Program, The exact rebate will depend on the specifics of each transaction and will be previewed for you prior to submitting each trade. This rebate will be deducted from your cost to place the trade and will be reflected on your trade confirmation. Order flow rebates are not available for non-options transactions. To learn more, see our Fee Schedule, Order Flow Rebate FAQ, and Order Flow Rebate Program Terms & Conditions.

Options can be risky and are not suitable for all investors. See the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options to learn more.

All investing involves the risk of loss, including loss of principal. Brokerage services for US-listed, registered securities, options and bonds in a self-directed account are offered by Open to the Public Investing, Inc., member FINRA & SIPC. See public.com/#disclosures-main for more information.