YouTube

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Today, we released a new podcast covering four underfollowed stocks that have generated monster returns for shareholders.

There are a few themes weaving these companies together. However, I was surprised to notice that all four could be described as roll-ups. Something to chew on.

Here are our notes for the episode, listen/watch for full analysis.

-Brett

Ryan #1: Lithia Motors

Lithia Motors is a retailer of new and used vehicles and related services. The company offers over 50 brands of vehicles at nearly 500 stores globally across the US and Canada. Basically they are a serial acquirer of automotive dealerships.

I don’t hear many people talk about this business, but they’ve put up phenomenal results for investors. They’ve beat the market over 10 years, 15 years, 20 years, you name it. Since their IPO in 1996, they have compounded at 13.5% per year for investors versus just 9% for the S&P 500.

They are currently the largest player in the industry, but still have an estimated 1.5% market share. This is a very fragmented market. There are 17,000 auto dealerships in the US. They have gone through that list, they have connections with these dealerships, they are waiting for the time that those dealerships are ready to sell. It reminds me a bit of Constellation Software in that way.

As for the actual existing business model, let me walk through how they make money and then we can talk about some of the advantages. When people think of car dealerships they probably think of buying and selling new and used vehicles, well Lithia Motors does that but it’s actually not the biggest part of their business. ~65% of the company’s gross profits come from Servicing and Financing. This serves them well during recessionary periods when people aren’t buying as many cars. In general, they run as normal dealerships and do everything a standard dealership does.

There are a couple distinct advantages to their business model.

For starters, throughout most of their history they have focused on dealerships in rural areas. These rural dealerships tend to have a local moat in that there are contracts with the OEM’s that prohibit someone from setting up a dealership for the same brand within a certain distance from an existing one.

There are size advantages as well. Unlike smaller dealers, they can centralize back-office functions and they don’t have to depend on consumer sentiment for a particular brand since they have almost all automotive brands under their portfolio.

Working capital advantages. By having multiple dealerships instead of a single location, they are able to move inventory around their storebase to help optimize certain stores.

They are typically able to acquire these dealerships at 0.25x sales. At Lithia’s 4% operating margins, that typically means they are paying ~6x expected earnings for those dealerships.

This formula has resulted in exceptional ROIC, and over time great EPS growth.

Question: If the returns on the acquisitions are so good, how come those returns have not been competed away by other capital providers?

Dealerships are auto companies’ touchpoints with consumers. Contractually, the franchisees are not allowed to sell to just anyone, it has to be approved by the parent brand. Lithia has become one of few companies who is actually seen as a good home for dealership franchises.

Lithia has a playbook that they can show to OEMs and say here’s how much volume growth we have been able to create post-acquisition in our previous deals, and that’s ultimately what the OEMs are looking for. They have the marketing fire-power and the know how to get more customers in the door, whereas a Private Equity buyer does not.

Question: If it’s such a good business, why does it trade at 9x earnings? What are the risks?

Rise of digital car buying marketplaces. Even though buying and selling used cars isn’t the biggest profit driver for Lithia, it’s an introduction to the customer. So customers that buy from them, then will also use them for financing and servicing down the line. If you strip away the first component, there’s risk that it impacts the rest of their business.

Rise of EVs. They have less moving parts. This could hurt Lithia’s Parts and Services segment which accounts for almost 40% of gross profit.

Beyond those longer-term worries, overall, I think investors just have concerns around interest rate sensitivity for Lithia. They think it might impact volumes, and Lithia’s cost of capital will rise. Net Debt to EBITDA is 7x, so they run quite levered because that’s how they like to acquire companies.

Question: What could happen in a world of increased tariffs?

Keep in mind, a good chunk of their profits come from more than just buying and selling cars so in general I think they will be alright in terms of revenue generation. Additionally, a big chunk of their costs like sales commissions are variable so they should be able to maintain profitability even in a tough environment. In previous recessions they’ve still been able to generate profits (2% operating margins in 2008).

Additionally, I think downturns can be a good share gain opportunity. Individual dealerships are not as well equipped to handle severe downturns so it’s likely that more of them will go up for sale (and likely at cheaper prices) if things turn sour.

Brett #1: Jack Henry & Associates

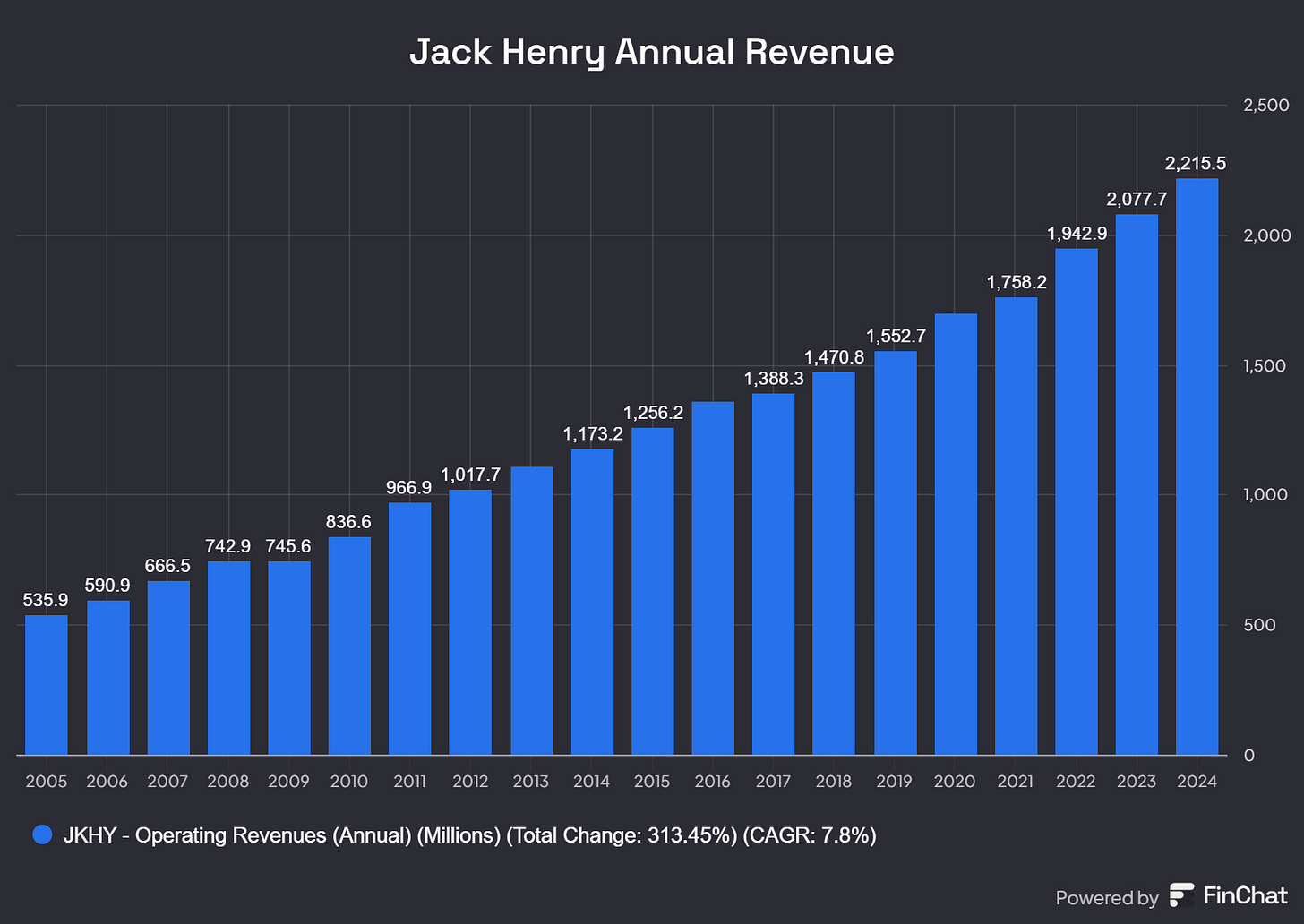

Jack Henry & Associates has generated a roughly 313,000% total shareholder return since 1990. That would have turned $10,000 into over $31 million in just over 30 years.

It has raised its dividend for 20 straight years. Revenue has grown every year since 2005. And yet, nobody talks about the stock.

Why?

Because it is the technical plumbing for small banks and credit unions (boring). Nobody interacts with the Jack Henry brands in everyday life. And yet, they may use a bank that is powered by its processing and back-end solutions.

“Core software systems primarily consist of the integrated applications required to process deposit, loan, and general ledger transactions, and to maintain centralized customer/member information. Our core banking solutions consist of three software systems marketed to banks, and our core credit union solution consists of one software system marketed to credit unions. These core systems are available for on-premise installation at client sites, or financial institutions can choose to leverage our private cloud environment for ongoing information processing.”

These are processes that a bank must get correct. Smaller banks probably do not have the development budget to build a well working system. This is where Jack Henry’s products step in.

Jack Henry has a long history of making strategic acquisitions, buying 35 companies to upgrade its product portfolio since 1999. I think this is a good lesson in acquisitions. There are few serial acquirers that can actually do well for shareholders. But those that do – Constellation Software, Berkshire Hathaway – make a killing for shareholders. Jack Henry looks to be in this rare mold.

Let’s break down how Jack Henry generates revenue.

First, the company separates out software, services, and support and processing revenue. As you can guess, processing is revenue associated with payments processing while the other segment is for the rest of the business.

Notice how long the contracts are for its software and services:

“Services and support includes: “private and public cloud” fees, which predominantly have contract terms of six years at inception; “product delivery and services” revenue, which includes revenue from the sales of licenses, implementation services, deconversion fees, consulting, and hardware; and “on-premise support” revenue, which is composed primarily of maintenance fees with annual contract terms.”

“Processing revenue includes: “remittance” revenue from payment processing, remote capture, and ACH transactions; “card” fees, including card transaction processing and monthly fees; and “transaction and digital” revenue, which includes transaction and mobile processing fees.”

Software/services revenue was $1.28 billion in 2024, making up 58% of sales. Processing revenue was $940 million in 2024, making up 42% of revenue.

Processing revenue has grown at twice the rate of software/services revenue in the last decade. This makes sense given it scales with the business + is inflation protected. Maybe this shows the untapped pricing power with the software solutions? This is something I would want to research further before owning the stock.

One thing to note: cloud revenue now makes up the majority of software/services revenue and has grown at an 11% clip in the last decade. Jack Henry has been able to adapt with the times, which is important for a technology-focused company to durably grow over the long haul.

Here is why I think Jack Henry stock is underfollowed:

Not a brand individual consumers interact with

Operates the back-end of an already boring industry (small banks and credit unions)

No explosive revenue growth to drive eyeballs

The name of the company does not indicate what the company actually does

Being underfollowed can be an advantage in stock performance, allowing the company to repurchase stock at cheap levels consistently or keep competitors ignorant of your cash cows.

Here is why I think Jack Henry stock has done so well for shareholders since going public:

Market share taker in a growing but boring niche. The number of small banks in the United States is shrinking, but the medium-to-large banks that Jack Henry serves are growing deposits. Jack Henry is taking share of this market that is seeing increasing demand because of how modern digital banking works. It is inflation protected (more processed volumes = higher revenues) and signs long-term deals.

Fantastic unit economics and consistent cash flow. Jack Henry has gross margins just north of 40% and operating margins consistently above 20%. Most of this operating profit is converted to cash flow, which has been positive year-after-year (see free cash flow per share chart). Consistency combined with durable growth lets compound interest work its magic.

Consistent and growing dividend payouts. Jack Henry keeps growing its dividend per share, which juices the total return figure. It does this each year. Its total return since 1990 is 313,000%, but the stock price is “only” up 173,000%. Dividend reinvestment helped double shareholder returns in this scenario.

I think the big lesson from Jack Henry’s performance is consistency. Yes, you need a good business that spits of cash flow. But just as importantly, you need a management team that is not going to waste that cash flow.

Ryan #2: Rollins

Like Lithia, Rollins has been an extremely successful roll-up in an unsexy industry. Rollins is a global leader in route-based pest control services for both residential and commercial customers.

To paint a picture on how well this stock has performed, if you would have invested $10,000 in Rollins in 1990, today you would have $1.4 million (15% CAGR). They have basically tripled the performance of the S&P 500 over the last 30 years.

Business Model: Rollins owns a number of pest control brands that are well-known within certain geographies. The customer journey often starts when someone experiences an issues with pests or termites. Most of the time, customers will want it taken care of right away so they will call their local pest control company (which is often a Rollins brand depending on where people live) and that will become the beginning of a longer-term relationship.

A technician at one of Rollins’ various brands like Orkin will get sent out to assess the property. They will then look for conditions that invite pests and will stop the spread by typically spraying some sort of chemical. This one-time visit, which solves an urgent issue for customers, then typically turns into an annual or semi-annual inspection just to make sure there isn’t anything that could become an issue later on.

As for the costs, this is predominantly a fixed cost business. About 80% of the costs for Rollins are fixed (labor, trucks, chemicals, equipment, etc.) which they are able to spread across a wider asset base compared to smaller player.

Like Lithia, this industry is full of smaller players. There are two giant companies that lead the industry, Rollins and Rentokil, which account for 24% and 30% market share respectively but then the rest of the industry is just 40,000 regional and local players. And as you can probably imagine, Rollins has all the standard economies of scale working for them. Can spend more on advertising, they’ve got centralized back office functions, better IT systems (which is huge for route optimization), and can spend more time/resources on training new technicians (they have a 27k sq foot training center in GA).

And because they have these scale advantages, they are able to make tons of bolt-on acquisitions at attractive prices relative to what the companies can earn under Rollins’ umbrella. In 2024, they acquired 32 new smaller players.

About 65% of their business is residential customers and 35% is commercial. All their customers are really quite sticky, and in most cases recurring. This is not a cost you’re going to skip out on even when times are tough.

So to sum up:

Recurring revenue that is resilient in tough times.

Better economics relative to smaller peers.

High fixed costs + scale advantages have created operating leverage. FCF margins have nearly tripled over the last 20 years.

What went right for Rollins shareholders?

Regionalization: By placing many smaller locations in a single region instead of one larger one, they have been able to get closer to the consumer and improve their economics by having the technicians spending less time on the road.

They did/do the hard stuff well: It’s one thing to say “oh we’re big, we have more money, we have an advantage over the smaller guys”. But that’s not enough. Great acquirers win with the details. Rollins has invested in great technician training, they have focused a ton on route optimization for technicians, they’ve created true national awareness for their brand, and all the other difficult things that go into actually integrating acquisitions.

Multiple expansion: This part is a little tough to identify but Rollins FCF multiple went from mid twenties to more than 40x, so this has certainly contributed to the returns.

Risks from here:

On the Lithia Motors section I asked, how come there hasn’t been competition from new acquirers? Well I’m asking the same thing here and the answer is that there has been. Private equity specifically has been pouring a lot of money into the pest-control business. I think this is a legitimate risk, maybe not just for the fact that they might lose out on bids, but that acquisitions will be more competitive and therefore more costly.

Brett #2: Amphenol Corporation

Since 1990, Amphenol Corporation has generated a total return of 63,000%. That would turn $10,000 into $6.34 million.

Hidden 100 baggers can be found by finding products that are a small part of an overall ecosystem/supply chain that the rest of the players in the sector cannot do without. Amphenol Corporation can literally be described as this with its interconnector products for electronics, automotive/aerospace, and industrial use cases.

It sells products such as simple point-to-point cables, power distributors, and sensors. If you work in automotive plants, science labs, or in the R&D department of a technology company, you will likely be using some Amphenol products

Like some of the other great 100 baggers, Amphenol has deployed a disciplined acquisition strategy, acquiring 50 companies in the last 10 years all focused on this one sector.

Amphenol’s history can be traced back to 1932 when a man named Arthur Schmitt founded American Phenolic Corporation to sell a molded rado tube socket that had better durability than existing products at the time.

In 1957, it listed on the New York Stock Exchange as Amphenol Electronics. I mention the early history because it looks to me like the company has been focused on one key niche throughout its history, a theme I think relates to Jack Henry too. Find a small profitable niche and stick to it.

Acquisitions have been at the heart of Amphenol’s strategy for a long time. In the 1960’s, it acquired a company called FXR in microwave technology, among many others.

It had a rough go of it in the 1970’s and early 80’s and was then bought out by private equity in 1987. By 1991, with costs in control Amphenol re-IPO’ed.

The last 30 years have been a fantastic time to lead the interconnect/sensor market. Everything is getting increasingly electrified with multiple tailwinds to drive long-term growth. I bet this is what drove the acquisition strategy to work so well, especially if you buy at a disciplined price.

You had:

Fiber optics. The internet/telecom boom has helped feed demand for Amphenol’s interconnectors. This continues to steadily grow.

IT/datacenters. Spending on datacenters means more spending on Amphenol products. The AI booms is likely helping them a ton.

Electrification of automotive/aerospace. Whether in military or commercial, these products are getting more advanced and more electric. That is a boon for Amphenol.

Electrification of manufacturing. The more we digitize and electrify manufacturing plants, the more Amphenol products are used. TSMC factories or automating the ports anyone?

No wonder Amphenol’s sales have steadily grown over the years. Revenue is up 3,570%, while free cash flow is up 13,120%.

Revenue has grown at a 12.3% annual rate since 2005 with only a few down years. Growth is a bit lumpier than Jack Henry, but that is due to the end markets.

Is there any reason for this end-market tailwind to stop? Amphenol doesn’t think so. Take the electric vehicle market, which is still a decade or two before becoming the majority of automotive sales in the United States.

Not even Tesla, which vertically integrates everything, is going to build its own connectors. And they don’t care whether the connectors are slightly higher in price every year, because it is a tiny part of the overall cost of its business.

So, what else drove Amphenol to become a 100 bagger? One factor may be multiple expansion. That stock currently trades at a P/E of 39. I doubt it traded at this level in 1995.

It looks like the company is a strategic repurchaser of stock. When the stock was in a large drawdown in the Great Financial Crisis, it started aggressively taking out its shares.

It has had improving free cash flow conversion (free cash flow growing faster than revenue). Better cash flow conversion opens up the balance sheet to be more aggressive on acquisitions at a lower cost of capital or returning more cash to shareholders. This is an underrated aspect of a high quality business.

Summing it up, here is how Amphenol crushed the market:

Played in an industry with rising market demands

Smart acquisitions at a reasonable price

Smart capital allocation and improving free cash flow conversion

Multiple expansion

We are not recommending to buy any of these four stocks today. We do not know enough about the companies, and they are likely either out of our circle of competence or overvalued. However, using these four examples as case studies can help us all identify promising stocks with 100 bagger potential.

I am looking for stocks that are market share takers, have a large industry tailwind or runway to grow, trade at a cheap price, have consistently good free cash flow conversion, and have strong capital allocators at the helm. Easier said than done.

All these factors can lead to rising free cash flow per share, which is the driver of stock returns over the long haul. A stock is worth the cash it produces for you, the shareholder.

Make sure to follow the show on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts, give us a 5 star review, and subscribe to the Substack to get our show notes.

Thank you to everyone who listened.

This is the best podcast "Chit Chat Stocks" has ever produced and one of the best ever on investing. Excellent illustration of these mid cap businesses, why its business model is profitable, and pros & cons to investing in each stock.