[PODCAST] Joel Greenblatt: The Intersection Of Quality And Value (Magic Formula For Stocks)

Learning from another superinvestor who crushed the market

YouTube

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Joel Greenblatt put up 50% gross returns at Gotham Capital, wrote two books on investing, and started Value Investors Club. It was a pleasure to study this superinvestor and what makes him successful.

You’ll never guess, but his secret is finding an intersection of quality and value that works for him. A stunning insight, I wonder if other investors have tried it?

Below, you can find our show notes from the episode.

-Brett

Who is Joel Greenblatt?

Joel Greenblatt is famous in the investing world for many reasons. He’s a very successful author, he’s one of the most well-known adjunct professors from the Columbia Business School for his value investing courses, he ran a fund of his own where he crushed the market for a decade straight, and he’s one of the founders of Value Investors Club.

Before we get into all that, let’s give a bit of background. Greenblatt was born in 1957 in New York. His father ran a shoe manufacturing company, which gave him an early understanding of the behind-the-scenes in running a business. He was always a strong student. He attended the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, which is where he became attracted to the stock market. And like many of the great investors in this era, Greenblatt was inspired initially by Ben Graham. Apparently, in his early years at Wharton, he read a Forbes article that laid out Graham’s rules for value investing, and it just clicked for him from there.

Like Graham, Greenblatt focused primarily on the quantitative aspects of securities. In 1981, at the age of 24, he wrote a Master’s thesis paper called “How the small investor can beat the market”. That paper was very successful and laid the groundwork for his first book “The little book that beats the market”.

Despite the interest in the stock market, after graduating from Wharton, Greenblatt went to Stanford for a year to study law. Within that year, he quickly realized that wasn’t what he wanted to do. Greenblatt moved back to the East Coast and took a job as an analyst at a small firm where it was just 3 partners and himself. It was while he was at that job that Greenblatt honed his focus on special situations. As the story goes, he was talking with a friend and mentioned that he thought he could run his own fund one day. That friend, I believe, worked for Michael Milken, who was considered the “Junk Bond King”.

The next day, Greenblatt’s friend called him back and said Michael wants to back you. Greenblatt flew out to the West Coast to negotiate a fee structure with Milken. Apparently, after difficult negotiations, Greenblatt received $7 million which served as the foundation for Gotham Capital.

Gotham Capital

In 1985, Greenblatt launched Gotham Capital. Gotham’s investor letters aren’t public record, but his returns are. From 1985 to 1994, Gotham Capital generated one of the best 10 year track records of all-time. He earned 50% annually on a gross basis and 34.4% on a net basis. That is truly exceptional.

And the best part is, there wasn’t some huge blow-up in 1994. Greenblatt decided in 1994 that he had become “sufficiently rich” and returned outside money to investors.

How he generated those returns isn’t 100% public information, but he does discuss his overall strategy and some of his successful investments in his book “You Can Be a Stock Market Genius”.

For a little bit of details on the fund, it was a long/short fund, and Greenblatt set it up where the first 20% annual returns had no fees, but then he got a 30% share of the profits from that point on. At least those were the terms with Michael Milken (might have changed for later investors).

And for those 10 years, Greenblatt earned his returns primarily through special situations.

Special Situations

Greenblatt broke down “special situations” into 4 categories in his book “You Can Be a Stock Market Genius”. If you’re really interested in becoming a better special situations investor, this book is a really nice primer and tells you what key aspects to look for in a potentially compelling special situation.

Spin-Offs

From what I can guess, spin-offs are likely the category where he made the majority of his returns. He knows these situations really well and he was particularly good at understanding management incentives related to spin-offs.

The general theme with spin-offs that seemed to be why he was so successful, is because once a company is spun off, there’s usually a disconnect among shareholders. Either it’s a small part of the business and certain investors can’t own companies that small, or it’s unrelated to why shareholders bought in the first place. Example: Altria spinning off Kraft Foods. I doubt most people bought Altria for their exposure to Mac & Cheese.

Greenblatt offers a 7 point checklist for spinoffs:

Spinoffs, in general, beat the market.

Picking your spots, within the spinoff universe, can result in even better results than the average spinoff.

Certain characteristics point to an exceptional spinoff opportunity:

Institutions don’t want the spinoff.

Insiders do want the spinoff.

A previously hidden investment opportunity is uncovered by the spinoff transaction.

You can locate and analyze new spinoff prospects by reading the business press and following up with SEC filings.

Paying attention to “parents” can pay off handsomely.

Partial spinoffs and rights offerings create unique investment opportunities.

Oh, yes. Keep an eye on the insiders.

One big lesson I took away from this part of the book. He didn’t really care what industry the companies were in. If it’s complex to him, it’s probably just as complex to everyone else, so he would always read the filings and try to understand the situation to the best of his ability.

Risk/Merger Arbitrage

Greenblatt isn’t fond of merger arbitrage. For those unfamiliar, “merger arbitrage” refers to the spread that exists between when a merger or acquisition is announced and when that merger actually closes. Typically, these exist because the company has to do further diligence on the acquisition candidate or they have to wait for regulatory approval.

But Greenblatt has said he was never fond of the low potential upside and high potential downside that came with this category. He did however like “Merger securities”. Here’s what he says “Although cash and stocks are the most common forms of payment to shareholders in a merger situation, sometimes an acquirer may use other types of securities to pay for an acquisition. These securities can include all varieties of bonds, preferred stocks, warrants, and rights.”

Like spinoffs, Greenblatt finds opportunities in this area typically because people don’t want them. If you invested in a company’s stock, and that company gets acquired, and all of the sudden you have some bond in a company you didn’t invest in in the first place, then you’re probably going to sell it.

Bankruptcy & Restructuring

Greenblatt explains that there are a number of reasons a company goes bankrupt beyond just “being a bad business”. Sometimes it’s mismanagement, sometimes it’s too much leverage, sometimes it’s a levered up acquisition. Whatever the reason, a company can go into chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and still be a decent business.

Here are his tips for analyzing bankruptcies:

Bankruptcies can create unique investment opportunities – but be choosy.

As a general rule, don’t buy the common stock of a bankrupt company.

The bonds, bank debt, and trade claims of bankrupt companies can make attractive investments – but first – quit your day job.

Searching among the newly issued stocks of companies emerging from bankruptcy can be worthwhile; just like spinoffs and mergers, bargains are often created by anxious sellers who never wanted the stuff in the first place.

Unless the price is irresistible, invest in companies with attractive businesses.

Selling Tips:

Trade the bad ones; invest in the good ones.

Recapitalization & Stub Stocks, Leaps, Warrants, and Options

I won’t spend too much time here, because you don’t really see recapitalizations any more so the chances to invest in stub stocks are quite rare. Just know that recaps were a tool used in the 80’s and 90’s to ward off hostile takeovers and that could create opportunities for some investors.

As for the derivatives, here’s what he says “There is a way to create your own version of a stub stock. Simply by choosing among the hundreds of available LEAPS, you can create an investment situation that has many of the risk/reward characteristics of an investment in the leveraged equity of a recapitalized company.”

Warrants, options, and LEAPs he basically groups into the same category and he says he only really used these when companies were “undergoing extraordinary corporate change”.

(Little Book) Buying Cheap

The whole point of Joel Greenblatt’s “Little Book” is finding high quality stocks trading at a cheap price. That’s it. Similar to Buffett, Graham, or even David Gardner, he wants to find an intersection between cheapness and durability that creates strong returns.

In order to quantify this dynamic, Greenblatt ran a study to see how a formulaic approach to the intersection of quality at a cheap price did vs. the broad stock market. As he highlights in the book, these returns were simply the first run in a back test and were not repeated with varying criteria in order to optimize the best results with 20/20 hindsight vision.

As you will see, the process was fairly simple.

He goes about it in an interesting way. First, we have to identify what it means for a stock to be cheap.

In his analysis, Greenblatt used the EV/EBIT multiple. This takes a stock’s current enterprise value and divides it by the trailing earnings before include interest and tax expenses.

The idea around this is simple, but perhaps today is as good as any to re-learn what might have been forgotten. If you buy a stock at a cheaper earnings multiple, you are getting a higher yield – hopefully with good cash conversion – coming onto the balance sheet that can then be returned to shareholders. An EV/EBIT of 5 is much better than 50, all else equal.

This would be the Graham, Schloss, pure deep value approach to the formula.

All Greenblatt did was take a list of every stock in his investable universe and rank it in order of EV/EBIT. So, if there were 1,000 stocks, the cheapest on EV/EBIT would get a ranking of 1, and the most expensive would get a ranking of 1,000.

How does the list look if we target EV/EBIT in public markets today?

Using our friends at Finchat.io, we can screen for stocks that have a cheap EV/EBIT fairly easily. The list below is from stocks that have an EV/EBIT below 5 and a market cap above $1 billion.

Recognize any names? Own any on this list? (First on the list is the cheapest EV/EBIT).

(Little Book) Buying Quality

From the Little Book:

“In short, companies that achieve a high return on capital are likely to have a special advantage of some kind. That special advantage keeps competitors from destroying the ability to earn above-average profits.”

This is another legendary investor talking about using data and price action to determine whether a stock has a competitive advantage. Gardner says that a stock that has done well should tell you something about the quality of a company. Greenblatt is using something similar, saying that high ROIC is the indicator of a competitive advantage.

You don’t need to start with trying to aimlessly find a competitive advantage. Use a return on capital filter to identify stocks that likely have a competitive advantage.

The two are connected. If you have a competitive advantage, you likely have durably high ROIC. If you don’t have a competitive advantage, why would you earn outsized returns vs. the competition?

Okay, let’s catch beginners up. What is ROIC? Return on invested capital is simply looking at earnings and dividing it by all the money invested in the business. That is “return” over “invested capital” and gets you a %.

In Greenblatt’s book, I assume he used EBIT as his earnings in order to keep things related to the cheapness factor. I am not sure what he used for invested capital, but the definition is not a big deal.

On Finchat.io, we can easily filter for ROIC. Here are the results for the highest ROIC companies with a market cap of over $1 billion (first is highest):

Notice any overlap? More on that later.

What is the Magic Formula? + Results

Combining the two factors together and we get Greenblatt’s magic formula. You rank stocks in the investable universe by cheapness and ROIC, with a 1 given to the cheapest stock and a 1 given to the stock with highest ROIC.

Then, you add the figures together for every stock. The 30 stocks with the lowest sum in the magic formula get put in the portfolio. You re-do the results and rebalance on a regular basis (I believe he rebalanced monthly).

How did the strategy do? With zero other rules, it absolutely crushed the market from 1988 to 2004. That is 17 years of outperformance.

From 1988 to 2004, the S&P 500 produced an annual return of 14%. That would turn $10,000 into $92,764.

Using the magic formula and getting a 33% return, that same $10,000 investment would turn into $1.3 million.

How I Use The Magic Formula Today With Finchat

I believe – and Greenblatt preaches in his lectures – that the magic formula should be a starting point in your true research on stocks. Use it, but then weed out value traps or stocks with unsustainable ROIC.

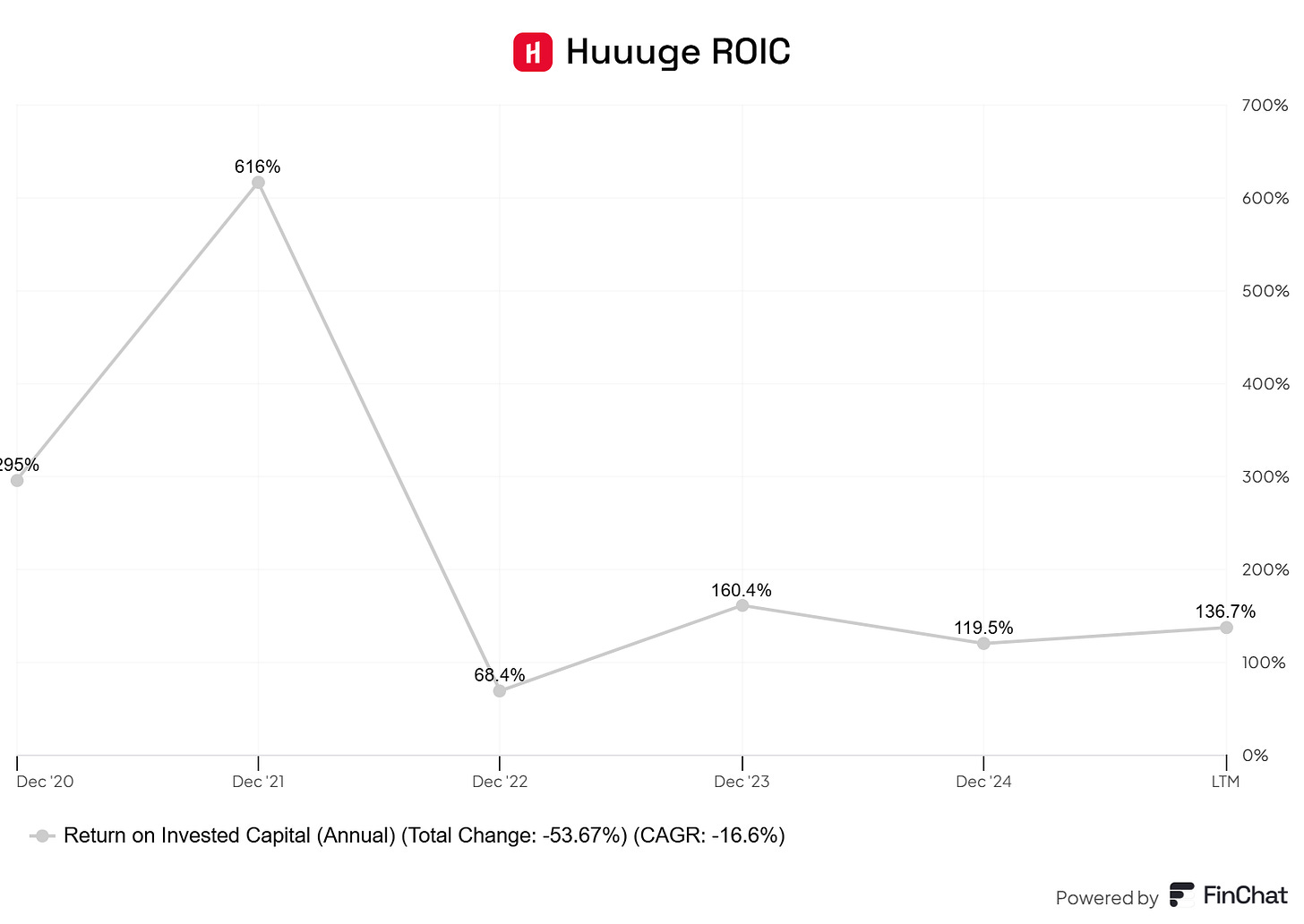

For example, we can look at one stock that made both of the lists above: Huuuge Inc. (ticker: HUG). I have never heard of this stock before, but I guess it is in mobile gaming.

Because I want to run a concentrated portfolio of stocks I understand, my research would not stop at the magic formula.

The stock trades at an EV/EBIT of 1.5. I would want to ask: why?

The stock has a high ROIC. I would want to ask: why?

Another way I can use the wonderful screener from Finchat.io is combining both ROIC and EV/EBIT into a single screener and using long term average ROIC to screen for durability.

We can also move into much smaller stocks.

There are 42 stocks at a market cap below $1 billion with a 10 year average ROIC above 15% and an EV/EBIT below 10. Sounds like a good hunting ground for value stocks!

This is as good of a list as any to begin your research journey. Unless you are an insane researcher like Buffett, there is always another stock to take a look at.

I will close with this quote from the Little Book that should get the intellectual electricity firing:

“So what should we be doing? Ideally, better than blindly plugin in last year’s earnings to the formula, we should be plugging in estimates for earnings in a normal year. Of course, last year’s earnings could be representative of a normal year, but last year may not have been a typical one for a myriad of reasons. Earnings could have been higher than normal due to extraordinarily favorable conditions that may not be repeated in most years. Alternatively, there may have been a temporary problem with the company’s operations, and earnings may have been lower than in a normal year.”

Don’t blindly follow the quant results. Leave that to the huge quantitative hedge funds.