[PODCAST] Li Lu - The Warren Buffett of China (How He Finds 100 Baggers)

What we learned from the legendary investor with a hard-to-believe life story

YouTube

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Today, we released a podcast covering Li Lu, the only investment manager Charlie Munger gave outside capital to.

Below are the show notes. If you enjoyed this episode, follow us and give the podcast a review on whatever podcast player you listen on.

Reminder! The Investing Power Hour is changing to a live recording on Thursdays at 5pm EST. Join us tomorrow evening and ask us questions!

Background (Ryan)

Li Lu has probably the most fascinating background of any investor we’ve ever studied.

He was born in Tangshan China in 1966 during Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution. As a part of the cultural revolution, Li Lu’s parents were sent to labor camps and Lu was forced to transition through various orphanages. And at the age of 10 he survived the Tangshan earthquake which apparently killed 240k people included all of Li Lu’s adoptive family.

If that wasn’t already an insane childhood, his life gets even crazier into his 20’s. In 1989, Lu who was attending Nanjing University at the time and had already majored in Physics, snuck onto a train heading to Beijing in order to participate in pro-democracy protests.

The protests and demonstrations (which included starving themselves) lasted for months and they eventually elected Li Lu as one of the leaders of the protests. According to one of the protest organizers “Li mostly remained silent during meetings, absorbing differing views. Li also made sure to get close to the right people.”

Li Lu was an outsider in these protests. He wasn’t from one of the prestigious Beijing universities and he didn’t have any ties to the organization. In fact many people in the protests were worried that he was a spy.

After a couple of months the protests had more than 1 million people that had joined in Tiananmen Square and for anyone familiar with this story, you likely already know what came next. Here’s a quote from a good Financial Times article on it:

“In the early hours of June 4, troops marched in, opening fire on activists. Tanks crushed tents with sleeping protesters inside and blocked exit routes, while soldiers arrested those who tried to flee. Officials claimed 200 civilians were killed; student leaders estimated the figure at up to 3,400.”

After that moment, the Chinese government named 21 people for the leading the uprising and Li Lu was one of them so he was forced to go into hiding. He escaped through a smuggling route and in 1989 he was granted asylum in the US.

In a memoir he wrote “I tried to identify with any family that took me in and learnt to fit into whatever environment I found myself”. He learned English within a single summer and enrolled at Columbia University where he earned a degree in economics while simultaneously earning graduate degrees in business and law. While at Columbia, he attended a lecture given by Warren Buffett which he says changed his life (sidenote: He apparently only attended the lecture because he misheard his friend and thought there was a free buffet.)

After attending that lecture he began investing his own money and generating good returns. So much so that in 1997 he decided to start his own fund.

Himalaya Capital/Guesses on Returns/Holdings (Brett)

Himalaya Capital was founded in 1997 by Li Lu after he finished business school. It is technically run out of Seattle, but Lu invests in Asia and North America with a focus on China, his home country. When looking up his 13F, you will see his American holdings but not anything listed in China or Hong Kong such as BYD.

Some stats on the fund:

In late 2023, it had $14 billion in AUM

Rumor has it they have put up 30% annual returns since inception (I cannot confirm that)

In 2004, Lu received an $88 million investment from Charlie Munger, who taught him the methods of “quality” value investing similar to Buffett.

Today, Himalaya Capital says it uses the value investing approaches of Ben Graham, Charlie Munger, and Warren Buffett. This is a combination of deep value investing and quality buy-and-hold investing.

He talks about the “wait for the fat pitch” approach and the Ted Williams analogy. However, he recommends investors focus on not being too patient and not swinging at all when the fat pitch presents itself.

Discussion Q: What investor downfall do you believe you need to work on the most?

“In making investments, I have always believed that you must act with discipline whenever you see something you truly like. To explain this philosophy, Buffett/Munger likes to use a baseball analogy that I find particularly illuminating, though I myself am not at all a baseball expert. Ted Williams is the only baseball player who had a .400 single-season hitting record in the last seven decades. In the Science of Hitting, he explained his technique. He divided the strike zone into seventy-seven cells, each representing the size of a baseball. He would insist on swinging only at balls in his ‘best’ cells, even at the risk of striking out, because reaching for the ‘worst’ spots would seriously reduce his chances of success.

As a securities investor, you can watch all sorts of business propositions in the form of security prices thrown at you all the time. For the most part, you don’t have to do a thing other than be amused. Once in a while, you will find a ‘fat pitch’ that is slow, straight, and right in the middle of your sweet spot. Then you swing hard. This way, no matter what natural ability you start with, you will substantially increase your hitting average. One common problem for investors is that they tend to swing too often. This is true for both individuals and for professional investors operating under institutional imperatives, one version of which drove me out of the conventional long/short hedge fund operation. However, the opposite problem is equally harmful to long-term results: You discover a ‘fat pitch’ but are unable to swing with the full weight of your capital.”

Today. It looks like Himalaya Capital is much more of a buy and hold patient investor than turning over deep value rocks. In the last 13F, it looks like they didn’t buy or sell any stocks (although that doesn’t include anything in China).

Besides that, we do not have much in public letters from Li Lu. With the performance of BYD stock, I would guess that the 30% return profile is not too far off from the long-term track record. We do not know for certain, though.

From a Columbia Business School talk not too long ago, he discussed some things that matter to him as an investor. We can talk about any of these, which include:

A great business is one with consistently high return-on-invested-capital (ROIC)

Addiction to a brand can be quite valuable (both literally and figuratively)

Himalaya Capital studies industries and looks for companies that are already strong, not ones they hope can be strong in the future

Durability of an investment can come from intelligent capital allocation by management

Here are other quotes from the talk I thought were interesting.

“Watch your portfolio go down 50% and not be affected. Watch everyone else make way more money than you and not get affected.”

“Financial markets are there to expose your weaknesses. If you don’t actually understand an investment, it will eventually expose you.”

“You are more likely to find promising investments in a rapidly growing economy.”

Timberland & Deep Value Philosophy (Ryan)

When you look into Himalaya Capital you will most likely hear the stories of the wonderful Chinese compounders that Li Lu identified early on. This is not one of those.

However, it’s a phenomenal example of his process and shows his flexibility as an investor.

In 1998, so this is before he had received any money from Charlie Munger, he came across an interesting idea through Value Line, a company called Timberland (no it has nothing to do with lumber).

Timberland was a clothing and shoes retailer that traded at a remarkably cheap multiple and had a phenomenal following with its core customers. When Li Lu found the company, Timberland was trading between $28-$30 per share and was estimated to be earning about $5 per share.

He also did some digging into the book value and assets of the company. He found that they had $300 million in operating assets, $100 million in cash, and $100 million in a commercial real estate building. He was also looking at this company during the 3rd quarter and knew that the 4th quarter was seasonally strong for cash flow, so there would be more cash at the company come the next report.

He found that it was a good enough business (he says 50% ROIC at the time) so he tried to figure out why it was so cheap and here’s what he discovered. The company was primarily owned by a family (40% of the shares, 98% of the voting power) and never raised any additional capital outside of its IPO – that means banks don’t have as much inclination to cover you.

The company also had a ton of outstanding lawsuits. He started going through each lawsuit and found that most of them were just upset shareholders who sued because the management team was missing guidance. Apparently those lawsuits were pissing off management enough that they stopped talking to wall street altogether which is part of why the company had no sell-side coverage.

The last sort of step of the process for Li Lu is getting a read on management. This is where he apparently goes to great lengths, and Lu has recommended to students in the past that they should operate like investigative journalists when assessing management. So Li Lu apparently started digging into the background of the CEO, found he had a son in business school, and determined that the son was set to succeed his dad as CEO.

He also found that the son served on the board of directors of a non-profit where Li Lu knew the founder. So Li Lu joined the board just to get connected with this son. Once he got to know the son, he introduced him to his dad and Li Lu was able to conclude that both were honest and competent people so he took a stake.

Over the next 2 years, Timberland jumped 700%.

BYD (Brett)

BYD is the largest electric vehicle maker in the world, headquartered in China. It has been the largest winner in the Himalaya Capital portfolio, which Lu said he has held for 22 years. The company is perhaps the closest thing we have to a vertically integrated clean energy company and has dominated the market through technological innovations and hard-nosed efficiency that Chinese manufacturers are famous for.

Here is a quote from a profile in the FT:

“Himalaya’s biggest early success bolstered that notion. In 2002, Li invested in BYD, then a little-known maker of electric batteries. Though he was still ostensibly forbidden from visiting the company’s factory in Shenzhen, he believed that the future lay in the manufacturing might of China and in the purchasing power of its 1.4bn consumers. He sold Munger on his vision, with Berkshire taking a 10 per cent stake in BYD in 2008. “I didn’t like the auto business,” Munger recalls. “It’s difficult to make a fortune in the auto business.” But, “it worked so well, the early investment in BYD was a minor miracle”. The company dethroned Tesla as the world’s biggest electric vehicle producer by sales last year.”

Here are some stats from our friends at Finchat.io.

29% revenue CAGR since 2005, $100 billion USD in revenue in 2024

Since 2002 it has been a 100 bagger, producing a 24% total return CAGR

BYD has been Li Lu’s defining bet, and made some money for his friends at Berkshire Hathaway while he was at it. The company is a classic “never sell” investment due to its reinvestment runway characteristics.

I know I am using a lot of quotes, but I cannot say it better than Lu in this investor talk:

“Another example is BYD, which we've held for 22 years. During this time, its stock has dropped by more than 50% at least six times, once even by more than 80%. Each significant price drop tests the boundaries of your circle of competence. Do you really understand it? Do you truly know its value and how much value it has created? In one year, BYD might have increased its value, yet its stock fell by 70%. Only then is your circle of competence truly tested; touching its boundaries confirms its existence. During the time we've held it, BYD's sales grew from one billion yuan to nearly one trillion yuan, and it hasn’t reached its limit; it continues to grow and create value. This is the intriguing part of investing.”

Discussion Q: What makes BYD a never sell investment vs. Timberland shoes?

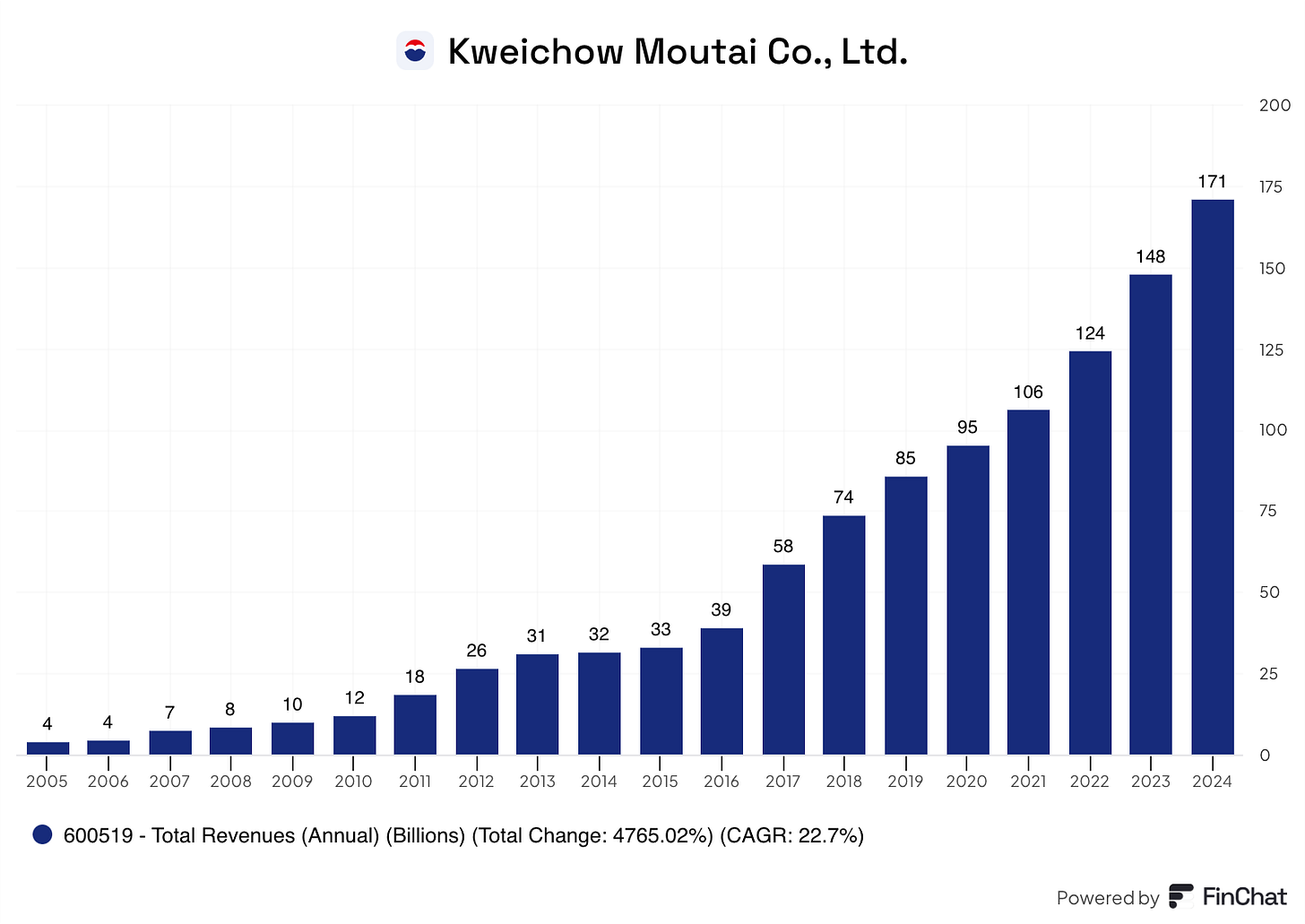

Kweichow Moutai (Ryan)

After Charlie gave Li Lu $88 million, he reportedly began buying up Kweichow Moutai right away.

Kweichow Moutai was a brand of distilled liquor that was very popular in China, especially after the communist revolution. According to that article from FT: “As China boomed, Moutai became the drink of choice for toasting foreign dignitaries and the bribe of choice for high-ranking bureaucrats.”

Here are some notes I found through a VIC writeup about the company:

“Kweichow Moutai’s main product is the Moutai alcoholic beverage. Moutai is the No.1 ranked premium baijiu (traditional Chinese liquor) in China. Moutai traces its roots back 2000 years ago to the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). From inception, it has gone through thousands of years of perfection and improvements. During the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), Moutai became the first Chinese liquor to be produced on a large-scale with an annual output of 170 tons. Today, Kweichow Moutai is one of the most recognized premium brands in China”

So it really is a cultural staple in China and it has seen remarkable growth in sales over the last 20 years:

So you’ve had a 48-fold increase in revenue, but the business model is remarkable as well. Premium Baiju is a really high-margin business (they’ve got 92% gross margins and 68% EBITDA margins), as the input costs are typically very low and they have a bit of a geographical moat as well since the grains required to make it are only grown in certain geographies.

In total they have grown EPS at a 26% CAGR over the last 20 years and the stock is more than a 300-bagger since 2004.

There isn’t a ton of color on his purchases or whether or not he still owns it as Himalaya is very discreet but Munger commented a bit on it in an interview. Munger says: “It was real cheap, four to five times earnings… And Li Lu just backed up the truck, bought all he could and made a killing.”

His Views on China & China/US Relations (Brett)

Given his historical rollercoaster relationship with the Chinese government, I feel that Li Lu takes a rational approach to China. He understands that market better than most in North America, but is not going to cheerlead for Chinese or U.S. investments just because that is where he is from.

In his early days running the fund, I found that Lu was extremely optimistic about China. He saw the growth in prosperity coming from the Cultural Revolution days, and the potential for more free markets to be a catalyst for a wealth boom for 1.5 billion people.

However, what has been interesting is his last talk, where his tone seemed to change. While he doesn’t directly criticize the government, I believe he is against the tighter capital controls and top-down commands from the government. He seems to think this will prevent China from escaping the middle-income trap.

What is the middle-income trap? It is the “trap” a country gets into at the start of industrialization, when a bunch of workers get higher incomes because of manufacturing jobs, but companies and sectors don’t grow much beyond this. Wage growth stagnates, as they have in Mexico and China in the last two decades. It is much more complicated than this, but I think people get the gist.

Here is what Lu says about escaping the trap:

“First, the perpetuating compound growth of a 3.0 economy [UNITED STATES] is powered by the free exchange and circulation of all economic elements within it. Every instance of free trade and exchange generates a synergistic effect, 1+1>2, while knowledge exchange can even achieve a multiplier effect, 1+1>4. Thus, the more frequent and unrestricted the exchanges of goods, services, and ideas, the greater the incremental benefits. A truly modernized and sustainable 3.0 economy possesses this crucial trait – the complete and unobstructed circulation of all elements, without any bottlenecks.”

Essentially, Lu says that free trade and free exchange of ideas are what help a country innovate and get out of the middle-income trap. Under Xi Jinping, the country has been moving in the wrong direction in this regard.

I wonder what he thinks of tariffs and trade wars?

Again, what I take away from this is that Lu cares about macroeconomics and political developments in China because it can inform him whether a stock is a good investment or not. BYD has been able to flourish and has been a leader in an industry that the Chinese government believes is a strategic priority. Add in a stunningly smart founder, and you have a win-win situation; no wonder the investment has done so well.

He seems to be more pragmatic about the situation between the United States and China as well as the domestic consumer depression in China. In his talk in December 2024, he essentially begs the Chinese government to stimulate consumer spending (a big factor holding back the economy), but says that you need to accept macroeconomic reality.

“As global investors, you need to invest in the most dynamic economies you believe in, but also pay attention to your actual needs so you can maintain your purchasing power where you consume. For global investors like Himalaya Capital, our goal is to select the most dynamic, creative, and competitive companies within the world's most vibrant economies, own their shares, and thus achieve the goal of maintaining and increasing wealth globally. However, for individual investors, you need to maintain your purchasing power in the economy where you are willing and need to consume, as that is your real wealth. For example, many Chinese investors' main purchasing needs are in China, and they may not need purchasing power in Europe or South America.”

Here is where I will close on this section. Both Ryan and I are pessimistic on China, but we usually give a shrug on the economy because it is one we have no competence in. Better to say you don’t know and not get exposure to that market. But Lu is an expert on this economy, and his views have gotten increasingly pessimistic in the last few years.

However, competence might be changing due to the macroeconomic paradigm shift, as he calls it. In fact, he believes it is so important that he is adding it as his sixth pillar of value investing.

“The sixth principle is what I'm sharing with you today, a conclusion based on the paradigm shift in civilization: the essence of wealth is the proportion of purchasing power in the economy, and the goal of value investing is to hold shares of the most dynamic companies in the most vibrant economies, thereby preserving and growing wealth. This principle is also the experience and contribution based on our practice at Himalaya Capital over the past thirty years.”

I think he is pessimistic right now, but says you need to focus on maintaining purchasing power so when the modern economic miracle (globally) eventually resumes, you can take advantage of that growth. Which is why you want to buy high-quality businesses at a discount.

Here are the six tenets of value investing:

A stock is not just a tradable piece of paper; it represents part ownership of a company.

Mr. Market is here to serve value investors

Investments must have sufficient margin of safety

Investors should have a clear circle of competence

Fish where the fish are (i.e. promising industries and economies)

Wealth is the proportion of purchasing power in the economy. The goal of value investing is to hold shares of the most dynamic companies in the most vibrant economics to preserve and growth wealth.

Lessons from Li Lu (Both)

(Brett)

Here is what I learned from Li Lu:

Understand the macroeconomic picture to inform your stock investing.

Worry about maintaining and growing your personal purchasing power.

If you don’t truly understand a company, the stock will eventually expose you.

Also, we can close with a fun story on meeting Bill Hwang, although it doesn’t fit into any sections.

“I will share a funny story. At that time, I was in New York exchanging views with several fund managers, one of whom was a Korean American. We discussed our investments, and he mentioned his interest in South Korea. I said I was also interested. At that time, the South Korean stock market had fallen by 80-90% in dollar terms, because not only did the stock market decline, but the Korean won also depreciated by 40-50%. He mentioned that he was making a transaction: buying POSCO, as its P/E ratio was only two, while simultaneously short-selling Samsung Electronics, because its P/E ratio was as high as three. He described this transaction as fantastic, the best investment opportunity he could find. This may sound crazy today, but it vividly reflected the mainstream Wall Street thinking back then and what went on outside of value investing. By the way, this person later became infamous by almost causing Credit Suisse to go bankrupt due to fraud, and he was recently sentenced to eighteen years in prison by a U.S. court.”

(Ryan)

Even though he sort of takes after Buffett, I feel like he has some similarities to David Gardner from when we studied him. Maybe I’m just thinking that because he’s let his winners run.

But one big take away I would steal here is to spend more time analyzing management. I’m not just talking about listening to conference calls. I mean try to hear what friends have to say, try to find if any VCs talked about them, try to see what they’re like outside of work. Get a real sense of who you are partnering with. I think that pretty much sums up his entire BYD investment.